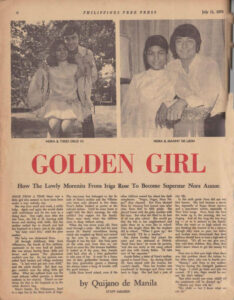

Golden Girl: When Nick Joaquin didn’t go bakya on Nora Aunor

The past several weeks saw Filipino film icon Nora Aunor at the center of the controversy over her exclusion from the list of winners of this year’s National Artist Award. After being nominated by the National Commission for Culture and the Arts, Aunor’s name was stricken off the final list by President Benigno Aquino III, who cited her history with drugs as the reason for the snub.

That controversy continues to hound Nora Aunor to this day comes as little surprise. Throughout her career, controversy has seemed to surround the actress since the beginning of her career.

That includes this classic profile written by late National Artist and Philippine literary legend Nick Joaquin, who penned the piece as Quijano de Manila for the Philippines Free Press in 1970 taking an in-depth look at the life of Nora Aunor. That the movie star, looked down upon as bakya by the literary elite of the day, was Joaquin’s subject drew brickbats from those snobs.

Joaquin would later discuss his decision to write about Nora Aunor, and the controversy it generated, in a speech for the Ramon Magsaysay Foundation.

“I remember this young poet scandalized by this article I did on Nora Aunor. Wrote this young poet: ‘Nick Joaquin is writing about Nora Aunor! Nick Joaquin has become a bakya writer!’ But that article lives as one of the best essays on Miss Aunor because she was not bakya to me and I did not go bakya on her,” Joaquin said.

There had always been something mythic about Nora Aunor’s origin tale, her rise from vending water beside railroad tracks in Bicol to becoming the superstar of Filipino film and music.

But to hear Nick Joaquin tell the story, it was positively magical.

Once upon a time there was a little girl who seemed to have been born under a very unlucky star.

She was born small and weak, a sickly baby. Again and again she would shake with convulsions and fix her eyes in a dying stare. One night, soon after she was born, she fell so ill, burning with fevers and shaking with chills, that her mother rushed her to church and had her baptized in a hurry, late in the night.

“My baby won’t live,” cried the poor mother.

The baby was christened Nora.

All through childhood, little Nora Villamayor, the fourth of five children continued to be very frail of health. She was always having those chills and fevers and spasms. The physicians couldn’t cure her. So, her parents consulted herb healers and village medicine men. “A bad wind got into your child,” said the witch doctors. But their magics couldn’t cure the ailing girl either. What she suffered from was the cruel sickness called poverty, a disease endemic in her country. There’s no medicine for that in the hospitals or in the witch doctor’s bag.

Nora’s family, the Villamayors, lived in a nipa hut in the Bicol town of Iriga. The two-room hut belonged to the family of Nora’s mother and the Villamayors were only allowed to live there. Nora’s father worked as porter at the railroad station. Until he came home at night with the day’s earnings, his wife couldn’t buy supper for the family. There were times when the children went to sleep without eating.

When she was seven years old, Nora went through a crisis. She had her most severe fit: fearful convulsions during which she coughed up blood and turned up her eyes in agony. Her parents thought it was the end. But Nora passed the crisis and, from then on, suffered no more fits. She became healthier. It looked as if the poor, thin, homely child had, after all, a fairy godmother because when this fairy godmother grants a blessing she always mixes a heap of trouble with the good fortune.

Little Nora loved school, even if the other children teased her about her dark complexion. “Negra, Negra, Nora Negra!” they chanted. But Nora shoed them by winning first honors year after year, from first to fifth grade. She played house with the girls, marbles with the boys. But what she liked to do best of all was play school. She would gather the tots in her neighborhood and make them sit in rows like in school. Then she taught them like the teachers did in school. “When I grow up,” she told herself, “I’ll be a teacher.”

The feature remains an immersive read to this day. At the heart of it, Nick Joaquin was able to capture in words the essence of what made Nora Aunor special.

HER STARRERS for Tower Productions, smash hits at the box-office, have turned Nora into a superstar, the superstar of the moment. She has broken the color line in Philippine movies, where the rule used to be that heroines must be fair of skin and chiseled of profile. Though neither fair nor statuesque, Nora has bloomed into a beauty all the more fascinating because it’s not standard. Seen close up, her complexion shows fine gold tints, her features reveal a delicacy of the outline, and her large liquid eyes are lovely. Her speaking voice is soft but always sounds full of emotions, even if she’s only asking you to sit down. Nobody who has been watching the local trend towards sexy and ever sexier stars would have predicted that the next pop goddess to dominate the scene would be a simple demure country girl.

Under the tutelage of director Artemio Marquez, Nora is also developing into quite an actress. She has poise, she moves naturally, she underplays rather than mugs. Best of all, she’s one local performer who knows how to react. A person present is mentioned in the dialogue, and her eyes automatically turn towards that person; or the ghost of a smile will flicker on her lips at certain words of somebody else’s lines. She seems to be really listening to the dialogue, to be paying attention to what’s happening on scene. Good acting is fifty per cent reacting. It seems to be instinctive in Nora. The stories she appears in are mostly foolish and fantastic, but hers is always a real presence, the impact of a live person. In one movie that had elves in it, she played a cripple hobbling about on a crutch, and because you could believe she was really a cripple you could almost believe in the elves too.

It was also fascinating to see Nick Joaquin, literary master, write about showbiz love triangles, in this case involving Nora Aunor, Tirso Cruz III, and Manny de Leon. He took a Twilight-esque debate between Team Tirso and Team Manny and treated it like the most serious of matters, staying true to his promise of never going bakya.

(W)hen she went into the movies she was paired with Tirso Cruz III. Box-office considerations were undoubtedly behind the campaign to project a Nora-Tirso romance, but what began as publicity may have evolved into, at least, a puppy-love affair. The consensus seems to be that Tirso wasn’t aggressive enough. When Nora became a star at Tower she got a new leading man, Manny de Leon. Again a romance was drummed up by the publicity department — but young Manny is the assertive type. The talk is that Nora was at first annoyed by the brash way he pushed himself in between her and Tirso; then she became rather charmed by the brashness, the quality that’s said to be missing in her other leading man.

Be that as it may, the rivalry has even her family taking sides. Her mother likes Manny for being so on the go; her elder sister thinks Tirso is the finer gentleman. The fans have split into two camps, Nora-Tirso versus Nora-Manny, and the war between the camps is for real. The Nora-Tirso camp bought that doll, Maria Teresa Leonora, for Nora; when they felt that Nora had broken off with Tirso they reclaimed the doll, handed it to Tirso. The Nora-Manny camp will go to see any Nora movie, even if Tirso is in it — “but we watch only Nora, not Tirso.” Maybe they close one eye.

For Nora herself, the war has brought private anguish. Her mother says that one night the girl came home in tears.

“Mamay, they’re saying that Tirso has had me and now Manny is having me! Would they like a doctor’s certification? If there’s so much malice in this business, maybe I should quit. We could go back to Iriga and I’d just do recordings. Oh, I’m glad my next role is a tomboy!”

Nora says that Tirson is just a good friend, Manny is just a good friend and: “I don’t think I’ll fall in love and marry until I’m 25.”

And she’s only 17 now.

News

“Beetroot for health: Eliminate anemia, cysts, and fibroids with this juice”

“Beetroot for health: Eliminate anemia, cysts, and fibroids with this juice” Natural remedies have proven to be an effective alternative…

“Perpektong Pamilya” Gumuho? Lucy Torres-Gomez, Umiibig sa Iba Habang Todo-Post Pa Rin ng Happy Family Photos!

“Perpektong Pamilya” Gumuho? Lucy Torres-Gomez, Umiibig sa Iba Habang Todo-Post Pa Rin ng Happy Family Photos! Kilalang-kilala bilang kalahati ng…

Any Husband Can Satisfy His Wife in Bed Thanks to This Powerful Combination

Any Husband Can Satisfy His Wife in Bed Thanks to This Powerful Combination Every man desires confidence and stamina in…

“Lucy Torres-Gomez, Nagnakaw Nga Ba?!” – Tsismis ng Shoplifting na Paulit-ulit Pa Ring Lumilitaw!

“Lucy Torres-Gomez, Nagnakaw Nga Ba?!” – Tsismis ng Shoplifting na Paulit-ulit Pa Ring Lumilitaw! Sa isang mundo kung saan ang…

SUNSHINE CRUZ: MULA SA SWEETHEART NG SHOWBIZ HANGGANG SA SENTRO NG MGA SCANDAL — BAKIT SUNOD-SUNOD ANG KONTROBERSIYA?

SUNSHINE CRUZ: MULA SA SWEETHEART NG SHOWBIZ HANGGANG SA SENTRO NG MGA SCANDAL — BAKIT SUNOD-SUNOD ANG KONTROBERSIYA? Akala ng…

NAPALUHA SI BIMBY SA HARAP NG PRESS! MALAKAS NA PAGBUBUNYAG TUNGKOL KAY KRIS AQUINO, NAKAKAGULAT ANG MGA NETIZENS

NAPALUHA SI BIMBY SA HARAP NG PRESS! MALAKAS NA PAGBUBUNYAG TUNGKOL KAY KRIS AQUINO, NAKAKAGULAT ANG MGA NETIZENS

End of content

No more pages to load